Asia Has Kept COVID-19 at Bay for 2 Years. Omicron Could Change That

0 View

Share this Video

- Publish Date:

- 25 January, 2022

- Category:

- Fitness

- Video License

- Standard License

- Imported From:

- Youtube

Tags

When the Omicron variant of COVID-19 emerged this fall, governments across East and Southeast Asia returned to a tried-and-true strategy to stop it: They doubled down on border restrictions. Japan banned entry for nearly all foreigners—including students who had already been admitted to universities. The Philippines barred foreign nationals arriving from countries with local Omicron cases. Thailand ended programs that allowed tourists to enter without quarantine.

But border closures did not stop the arrival of the Omicron variant. Multiple countries across Asia are reporting spiking infections. Japan’s COVID-19 cases hit 20,000 a day, approaching the record tallies caused by the Delta variant in August. In the Philippines, daily case totals hit nearly 37,000—almost double previous highs in September. COVID-19 cases in Singapore and Indonesia have begun to rise, though they are not yet surging. [time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

In the third year of the COVID-19 pandemic, borders across the region remain heavily restricted. But many experts question whether continuing to stay closed to tourists, students and business travelers is an effective strategy for reducing COVID-19 now that Omicron has taken over—given the evidence that it is more contagious, though potentially with less severe symptoms.

“There’s very little [effect] that border closure and all that would have in terms of the impact in preventing the introduction of Omicron into various countries,” says Dr. Ooi Eng Eong, an infectious disease expert from the Duke-National University of Singapore Medical School. “This is how a very infectious virus will spread, but there’s actually very little that we can do to prevent it, except for vaccinating populations.”

Why Asia was successful

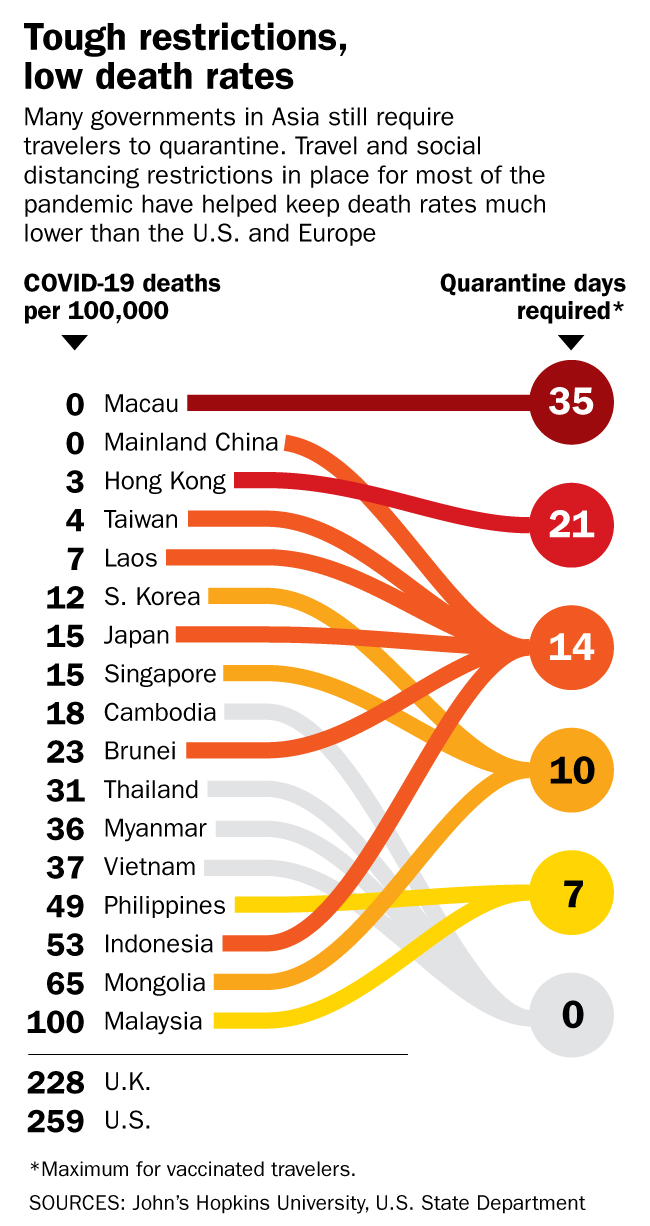

Lon Tweeten/TIMEAs the COVID-19 pandemic enters its third year, most of East and Southeast Asia remains closed to travelers. Border restrictions helped the region fend off COVID-19 at the start of the pandemic, but they are not stopping the arrival of the Omicron variant.

Asia’s COVID-19 strategies—border closures, quarantine requirements, a pervasive mask-wearing culture, coupled with vaccination campaigns—have worked extremely well so far. Japan, which struggled with a wave of the Delta variant following the Tokyo Olympics, has recorded 15 deaths per 100,000 people, while South Korea has had 12 deaths per 100,000. Hong Kong, which has continued to pursue a “zero COVID” strategy of eliminating all infections, has reported fewer than 13,000 cases across its 7.5 million people, and its death rate is 3 per 100,000 people. In mainland China, where COVID-19 was first detected, just 4,600 deaths have been reported among 1.4 billion people—a death rate close to zero. In contrast, 259 people have died per 100,000 in the U.S. The death rate in Germany, which has won praise among large European nations for its handling of COVID-19, is 139.

In countries with high vaccination rates—like Japan, where nearly 80% of the population is fully vaccinated—experts expect deaths to remain low during the Omicron wave, even if infections spike significantly higher than in previous waves. The number of infections per capita in Japan remains low compared to Europe and the United States—this may be evidence of the effectiveness of vaccines, masks, and social distancing,” Dr. Taro Yamamoto, a professor of international health at Nagasaki University, says.

However, Hong Kong is taking no chances. The city’s COVID-19 entry restrictions were already some of the tightest in the world, including mandatory 21-day quarantine for most travelers. It took just a handful of Omicron infections in the community—believed to have originated from two Cathay Pacific Airways flight attendants who were later fired and then arrested—for borders to close even tighter. The financial hub, which once boasted one of the world’s 10 busiest airports, has now banned all flights from eight countries including the U.S. and the U.K. and also barred travelers from more than 150 countries and territories from taking connecting flights through the city.

Fewer than 100 cases of Omicron have been found in the city to date. Yet just five days into 2022, Chief Executive Carrie Lam announced social distancing restrictions reminiscent of those imposed in 2020—the closure of gyms, spas and other businesses that require close contact between customers and providers; strict limits on the number of people who can gather in public; and a 6 p.m. curfew for restaurant dining. Some 3,000 travelers and close contacts of infected people are being held at a government quarantine center outside Hong Kong Disneyland.

Weighing the costs of border closures

Lon Tweeten/TIMECOVID-19 death rates across Asia have been dramatically lower than the rates seen in the U.S. and Europe.

The Chinese territory’s zero tolerance for COVID-19 cases is motivated at least in part by Beijing’s requirements for reopening the border with mainland China—which has itself enacted aggressive lockdowns, testing and tracking to keep out COVID-19.

But these border closures came at a cost. For Hong Kong, the three-week quarantine crippled its status as a global tourist destination and travel hub. International tourism is a major contributor to Thailand’s economy, which shrank by 6% in 2020, according to the World Bank, and was estimated to increase by only 1% in 2021. Tourism-dependent businesses across Asia took the hit. Lee Kyusung, a bar owner from Seoul in South Korea, said he saw less of his expatriate customers, who made up at least 40% of his usual crowd.

While some places, like Singapore, have reopened borders for vaccinated travelers from other countries, most have imposed restrictions on travelers regardless of vaccination status. That’s because growing evidence shows that current vaccines are less effective at stopping the spread of Omicron than of previous variants. Even so, they remain effective at preventing severe COVID-19 and death.

The good—and bad—news about vaccines

Complicating matters, a small-scale study suggests one of the most common vaccines in the region could be especially ineffective at stopping Omicron’s transmission. The lab study by Hong Kong University and the Chinese University of Hong Kong scientists in November analyzed blood samples from 25 patients vaccinated with two shots of CoronaVac—an inactivated vaccine made by China’s Sinovac. It found none of the samples produced enough neutralizing antibodies to stop the Omicron variant. For the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine, only five out of 25 samples produced enough antibodies. (More neutralizing antibody levels are thought to provide more protection against symptomatic COVID-19.)

Sinovac’s shot is one of the two vaccines widely used in China, where 2.9 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses have been administered. It is also the most used vaccine in Indonesia. The Philippines received more than 50 million doses of the vaccine from China.

But Leo Poon, of the University of Hong Kong, says that policymakers should take into account data from other countries, which shows Omicron surges are likely to put less stress on health care systems if the population is highly vaccinated. “I think that that is good news, and this is the most important message,” he says. “Everyone has to understand that.”

For countries with high vaccination rates, like Japan, many infectious disease experts are saying it’s time for politicians to drop tough restrictions on international travel. “Japan’s approach to border control—shutting down borders—does not make sense any more,” says Kenji Shibuya, Research Director of the Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research. “I think that it is a political gesture.”

Not every country has that luxury. Indonesia, the fourth most populous country in the world, has fully vaccinated just 43% of its 274 million people, according to World Health Organization data. The Philippines has a vaccination rate of 47%. In conflict-ridden Myanmar the rate is 30%.

“We need to try to help these people,” Poon says. He appeals to countries with surplus jabs to do more: “If you have vaccines, then please make them available to other people.”