Ozempic for weight loss: What coaches (and clients) need to know about GLP-1 drugs

0 View

Share this Video

- Publish Date:

- 20 May, 2024

- Category:

- Fitness

- Video License

- Standard License

- Imported From:

- Youtube

Tags

ngela Fitch’s family history of obesity caught up to her at age 40, when she was pregnant with her first child.

As a physician and obesity medicine specialist, Dr. Fitch knew the lifestyle levers to pull—and she had the financial means to yank them hard.

After giving birth, she lifted weights with a trainer twice a week. She sweated through one Peloton workout after another and tracked her food intake on MyFitnessPal.

Nevertheless, for the next decade, Dr. Fitch lost (and regained) the same five to ten pounds. Her blood pressure crept upward. Then came a sleep apnea diagnosis.

As her 50th birthday neared, Dr. Fitch decided to take the advice she gave her patients. She went on medication. (And, she lost 30 pounds.)

In the years since, Dr. Fitch has occasionally stopped her meds. For a few months, she maintains her results.

Eventually, however, the scale climbs back. For now, she’s decided that she’ll be on medication long-term.

If you’re a coach, how does this story land with you?

Does it…

… Make you feel disappointed? Does this seem like a story of someone “giving up” or “not trying hard enough”?

… Inspire you with a sense of awe? That modern medicine has figured out how to treat yet another chronic disease?

… Bring up questions? Like wondering about the effects of being on medication—potentially long-term? (Or if weight loss is even that relevant—so long as a person is eating healthy and exercising regularly?)

Dr. Fitch is now president of the Obesity Medicine Association and chief medical officer of Known Well, a primary care and obesity medicine practice in Needham, Massachusetts. Regardless of how you feel about her story, it illustrates what can initially seem like an inconvenient truth for those of us in the health coaching industry:

Behavior change on its own isn’t always enough.

For many people with obesity, semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy, Rebelsus), tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound), and other glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) serve as valuable tools that make significant and lasting weight loss possible.

But for health coaches, these drugs can seem like an existential threat.

You might wonder:

‘Who needs a nutrition coach or a personal trainer when people can get faster, easier, and more dramatic results with drugs?’

However…

People need health coaches now more than ever.

In this story, we’ll explain why—and show you how to turn “the golden age of obesity medicine” into a massive career opportunity.

With fat loss, there’s no such thing as an “easy way out.”

To manage diabetes or treat cancer, most people consider it normal and natural to combine lifestyle behaviors with prescription medicine.

No one would tell someone with cancer, “You’re on chemo? Way to take the easy way out!”

However, that’s what many people with obesity hear when they mention medication or surgery.

For decades, much of society hasn’t viewed obesity as the disease that it is.

Instead, people have seen it as a willpower problem.

The remedy: “Just try harder.”

However, rather than motivating people to succeed, this “remedy” often encourages them to give up. (More importantly, the willpower theory isn’t based on science.)

In reality, people with obesity likely have as much willpower as anyone else.

However, for them, fat loss is harder—because of genetics and physiology, along with social, cultural, behavioral, and/or environmental factors that work against them.

Why is it so difficult to lose fat?

Imagine life 150 years ago, before the invention of the automobile. To get from point A to point B, you had to walk, pedal a bicycle, or ride a horse.

Food was often in short supply, too. You had to expend calories to get it, and meals would just satisfy you (but not leave you feeling “full”).

Today, however…

“We live in an obesogenic environment that’s filled with cheap, highly-palatable, energy-dense foods [that make overeating calories easy, often unconsciously], and countless conveniences that reduce our physical activity,” says Karl Nadolsky, MD, an endocrinologist and weight loss specialist at Holland Hospital and co-host of the Docs Who Lift podcast.

You might wonder: Why do some people gain fat in an obesity-promoting environment while others don’t?

The answer comes down to, in large part, genetics and physiology.

(Obesity is complex and multifactorial. As we noted above, there are other influential factors, but your genes and physiology are mostly out of your control, and so medication might be the best tool to modify their impact.)

Genetically, some people are more predisposed to obesity.

Some genes can lead to severe obesity at a very early age. However, those are pretty rare.

Much more common is polygenic obesity—when two or more genes work together to predispose you to weight gain, especially when you’re exposed to the obesogenic environment mentioned earlier.

People who inherit one or more of these so-called obesity genes tend to have particularly persistent “I’m hungry” and “I’m not full yet” signals, says Dr. Nadolsky.

Obesity genes also seem to cause some people to experience what’s colloquially known as “food noise.”

They feel obsessed with food, continually thinking, “What am I going to eat next? When is my next meal? Can I eat now?”

Physiologically, bodies tend to resist fat loss.

If you gain a lot of fat, the hormones in your gut, fat cells, and brain can change how you experience hunger and fullness.

“It’s like a thermostat in a house, but now it’s broken,” says Dr. Nadolsky. “So when people cut calories and weight goes down, these physiologic factors work against them.”

After losing weight, your gut may continually send out the “I’m hungry” signal, even if you’ve recently eaten, and even if you have more than enough body fat to serve as a calorie reserve. It also might take more food for you to feel full than, say, someone else who’s never been at a higher weight.

Enter: GLP-1 drugs

In 2017, semaglutide—a synthetic analog of the metabolic hormone glucagon-like peptide 1—was approved in the US as an antidiabetic and anti-obesity medication.

With the emergence of this class of drugs, science offered people with obesity a relatively safe and accessible way to lose weight long-term, so long as they continued the medication.

How Ozempic and other obesity medicines work

Current weight loss medications work primarily by mimicking the function of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), which is a hormone that performs several functions:

In the pancreas, it triggers insulin secretion, which helps regulate blood sugar.In the gut, it slows gastric emptying, affecting your sensation of fullness.In the brain, it reduces cravings (the desire for specific foods) and food noise (intrusive thoughts about food).In people with obesity, the body quickly breaks down endogenous (natural) GLP-1, making it less effective. As a result, it takes longer to feel full, meals offer less staying power, and food noise becomes a near-constant companion, says Dr. Nadolsky.

Semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy, Rybelsus) and medicines like it flood the body with synthetically made GLP-1 that lasts much longer than the GLP-1 the body produces. This long-lasting effect helps increase feelings of fullness, reduce between-meal hunger, and muffle cravings and food noise.

Interestingly, by calming down the brain’s reward center, these medicines may also help people reduce addictive behaviors like problem drinking and compulsive gambling, says Dr. Nadolsky.

The lesser-known history of weight loss medicine

To understand the power of semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy, Rybelsus) and other GLP-1 medicines, it’s helpful to know a little about the drugs that predated it.

Decades before the age of Ozempic, physicians realized that several drugs originally developed to treat other conditions also seemed to help people lose weight.

These included:

Qsymia, which pairs phentermine (an older weight loss medicine) with the epilepsy medicine topiramateContrave, which combines the antidepressant bupropion (Wellbutrin) with naltrexone, used to treat addictionsMetformin, a diabetes medicineHowever, weight loss from these older medicines was modest, helping people to lose (and keep off) around 5 to 10 percent of their body weight.1 2 3

Around 2010, liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda) was approved by the FDA to treat diabetes. Like Ozempic and other newer weight loss medicines, liraglutide mimics glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), but it’s less effective than the newer medicines.

Why does Ozempic get all the credit?

Ozempic has become the Kleenex of weight loss medicines—a name brand people toss around as if it’s generic.

This fame is at least partly earned: Dr. Fitch says that semaglutide (Ozempic, Rybelsus, Wegovy) also works more effectively than liraglutide, its GLP-1 predecessor.

“Semaglutide is 94 percent similar to our own GLP-1,” she says, “They’ve been able to make it closer and closer to the GLP-1 our bodies make.”

It also lasts longer than liraglutide, and more of it reaches the brain.

However, newer meds outperform Ozempic. (See the table in the section below.)

And there are other medicines—available orally rather than via injection—coming. These pills will be easier to mass produce, which will drive down costs and make GLP-1 medicines even more accessible to more people.

So, although Ozempic is the current reigning brand of the weight loss drug world, it may be ousted in time.

The growing effectiveness of weight loss drugs (especially in combination with lifestyle modifications)

Researchers measure a weight-loss medicine’s success based on the percentage of people who reach key weight loss milestones.

For example, most people start to see health benefits after losing five percent of their weight—and remission from disease after losing around 20 percent.

As the chart below shows, weight loss medicines have become increasingly effective at helping people to reach both milestones.

Medicine% of people who lose 5% of their weight% of people who lose >20% of their weightFirst-generation weight loss medicines (Qsymia, Contrave, Metformin) 4 5 653-80%10-20%Semaglutide (Ozempic, Rybelsus, Wegovy) 7 886%32%Tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) 9 1085-91%50-57%Retatrutide (not yet FDA approved) 11 1292-100%80-83%How do weight loss medications compare to traditional interventions?

In the past, weight loss interventions have focused on lifestyle modifications like calorie or macronutrient manipulation, exercise, and sometimes counseling.

Rather than pitting lifestyle changes against weight loss medicines or surgery, it’s more helpful to think of them all as tools.

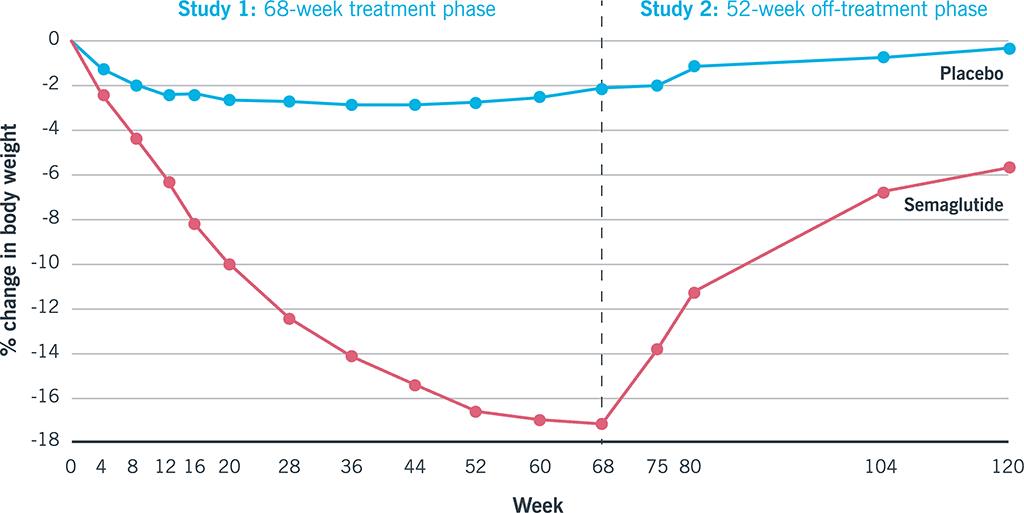

As the graph below shows, the more weight loss tools someone uses—including coaching—the more significant the results.13 14 15 16

Fat loss often comes with powerful health benefits

For years, the medical community has told folks that losing 5 to 10 percent of their body weight was good enough.

Partly, this message was designed to right-set people’s expectations, as few lose much more than that (and keep it off) with lifestyle changes alone.

In addition, this modest weight loss also leads to measurable health improvements. Lose 5 to 10 percent of your total weight, and you’ll start to see blood sugar, cholesterol, and pressure drop.17

However, losing 15 to 20 percent of your weight, as people tend to do when they combine lifestyle changes with second-generation GLP-1s, and you do much more than improve your health. You can go into remission for several health problems, including:

High blood pressureDiabetesFatty liver diseaseSleep apneaThat means, by taking a GLP-1 medicine, you might be able eventually to stop taking several other drugs, says Dr. Nadolsky.

Experts suspect GLP-1s may improve health even when no weight loss occurs.

“The medicines seem to offer additive benefits beyond just weight reduction,” says Dr. Nadolsky.

Research indicates that GLP-1s may reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events (heart attacks and strokes) in people with diabetes or heart disease.18 19 20In people with diabetes, they seem to improve kidney function, too.21

The theory is that organs throughout the body have GLP-1 receptors on their cells. When the GLP-1s attach to these receptors in the kidneys and heart, they seem to protect these organs from damage.

For this reason, in 2023, the American Heart Association listed GLP-1 receptor agonists as one of the year’s top advances in cardiovascular disease.

Ozempic side effects

You’ve likely heard that slowed gastric emptying from GLP-1s can lead to nausea, constipation, and other GI woes.

That’s all true.

However, for most, these side effects are manageable, especially with the help of a few key strategies (which we’ll cover later).

For now, however, we’d like to hash out a particular downside you’ve likely heard about from the media—because it offers a huge opportunity for health coaches.

When people take GLP-1 weight loss medicines, about 30 to 40 percent of the weight they lose can come from lean mass.22 23 24

Put another way: For every 10 pounds someone loses, about six to seven come from fat and three to four from muscle, bone, and other non-fat tissues.

This statistic has been broadcast among many media outlets in recent weeks as a dire warning against taking Ozempic, Wegovy, or Zepbound.

Such stories often fail to mention two important caveats:

Caveat #1: People with severe obesity generally have more muscle and bone mass than others.

To understand why, imagine you were forced to wear a 100- or 200-pound body suit every day for a year. Everyday activities—getting in and out of chairs, walking to and from the mailbox, climbing steps into a building—would feel like a resistance workout.

That’s likely partly why bariatric surgery patients experience a nine-year extension on their life expectancy, despite 30 percent of their weight loss coming from lean mass. They have more muscle than average to begin with, and therefore can safely lose some.25 26

For people with severe obesity, the health boost from body fat loss offsets the health risk of muscle and bone loss, says Dr. Fitch.

That said, there’s a caveat to the caveat: People who are only 30 pounds or so overweight may not be starting out with muscle and bone mass to spare. Especially if they’re older, they may begin their weight loss journey already under-muscled, with relatively low bone density. In those people, another drop in lean mass and bone density can add up to big health problems.

However…

Caveat #2: Muscle and bone loss aren’t inevitable.

As Dr. Nadolsky puts it, “Muscle loss isn’t a reason to avoid treating obesity [with medication]. It’s a reason to do more exercise.”

This is where coaches can shine.

By showing clients how to adopt muscle-building behaviors like strength training, combined with adequate protein consumption, you can help people offset the worst of the side effects when taking these medicines.

The yo-yo problem

GLP-1s are expensive, costing roughly $1000 USD a month. As a result, many insurers either refuse to cover them or limit their coverage to a year or two.

Once the money runs out, people tend to go off the meds—and the hunger and cravings return.

If they’ve done little to change their foundational eating habits, this puts them at a significant disadvantage. If they’re not eating slowly and mindfully and improving satiety with veggies and lean protein, the return of hunger and food noise can be overpowering.

That’s likely why, in one study, participants who stopped taking semaglutide regained, on average, two-thirds of the weight they’d lost.27

Again, here’s another opportunity for coaches…

Use weight loss medicine as a key that unlocks lifestyle changes.

Weight loss medicines don’t render behavior-based strategies obsolete; they make them more critical.

When GLP-1 medicines muffle food noise and hunger, your client will find it easier to prioritize protein, fruits and veggies, legumes, and other minimally processed whole foods. Similarly, as the scale goes down, clients feel better, so they’re more likely to embrace weight lifting and do other forms of exercise.

According to a 2024 consumer trends survey, 41 percent of GLP-1 medicine users reported that their exercise frequency increased since going on the medication. The majority of them also reported an improvement in diet quality, choosing to eat more protein, as well as fruits and vegetables.28

This is great news, because, as mentioned above, lifestyle changes are critical to preserving lean mass and preventing regain, should clients choose to discontinue medication.

When working with clients on GLP-1s, keep the following challenges in mind.

Coaching strategy #1: Find ways to eat nutritiously despite side effects.

The slowed stomach emptying caused by GLP-1 drugs can trigger nausea and constipation.

Fortunately, for most people, these GI woes tend to resolve within several weeks.

However, if you’re working with a client who’s experiencing a lot of nausea, they won’t likely welcome salads into their lives with open arms. (Think of how you feel when you have the stomach flu. A bowl of roughage doesn’t seem like it’ll “go down easy.”)

Instead, help clients find more palatable ways to consume nutritious foods. (For example, fruits and vegetables in the form of a smoothie or pureed soup might be easier.)

Dr. Nadolsky also suggests people avoid the following common offenders:

Big portions of any kindGreasy, fatty foodsHighly processed foodsAny strong food smells that trigger a client’s gag reflexSugar alcohols (like xylitol, erythritol, maltitol, and sorbitol, often found in diet sodas, chewing gum, and low-sugar protein bars), which can trigger diarrhea in someCoaching strategy #2: Prioritize strength training.

To preserve muscle mass, aim for at least two full-body resistance training sessions a week.

In addition, move around as much as you can. Walking and other forms of physical activity are vital for keeping the weight off—and can help to move food through the gut to ease digestion.29 30

(Need inspiration for strength training? Check out our free exercise video library.)

Coaching strategy #3: Lean into lean protein.

In addition to strength training, protein is vital for helping to protect muscle mass.

You can use our free macros calculator to determine the right amount of protein for you or your client. (Spoiler: Most people will need 1 to 2 palm-sized protein portions per meal, or about 0.5 to 1 gram of protein per pound of bodyweight per day.)

Coaching strategy #4: Fill your plate with fruit and veggies.

Besides being good for your overall health, whole, fresh, and frozen produce fuels you with critical nutrients that can help drive down levels of inflammation.

In addition to raising your risk for disease, chronic inflammation can block protein synthesis, making it harder to maintain muscle mass.

(Didn’t know managing inflammation matters when it comes to preserving muscle? Find out more muscle-supporting strategies here: How to build muscle strength, size, and power)

Coaching strategy #5: Choose high-fiber carbs over low-fiber carbs.

Beans, lentils, whole grains, and starchy tubers like potatoes and sweet potatoes are more likely to help clients feel full and manage blood sugar than lower-fiber, more highly processed options.

(Read more about the drawbacks—and occasional benefits—of processed foods here: Minimally processed vs. highly processed foods.)

Coaching strategy #6: Choose healthy fats.

Healthy fats can help you feel full between meals and protect your overall health. Gravitate toward fats from whole foods like avocado, fatty fish (which is also a protein!), seeds, nuts, and olive oil—using them to replace less healthy fats from highly processed foods.

(Not sure which fats are healthy? Use our 3-step guide for choosing the best foods for your body.)

Coaching strategy #7: Build resilient habits.

It may go without saying, but the above suggestions are just the start.

(There’s also: quality sleep, social support, stress management, and more.)

Most importantly, clients need your help to make all of the above easier and more automatic.

And that’s the real gift of coaching: You’re not merely helping clients figure out what to eat and how to move; You’re showing them how to remove barriers and create systems and routines so their road to health is a little smoother.

That way, if they do need to stop taking medication, their ingrained lifestyle habits (that the medicine made easier for them to adopt) will make it more likely that they maintain their results.

jQuery(document).ready(function(){ jQuery("#references_link").click(function(){ jQuery("#references_holder").show(); jQuery("#references_link").parent().hide();>References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

Hendricks EJ. Off-label drugs for weight management. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2017 Jun 10;10:223–34.Lonneman DJ Jr, Rey JA, McKee BD. Phentermine/Topiramate extended-release capsules (qsymia) for weight loss. P T. 2013 Aug;38(8):446–52.Sherman MM, Ungureanu S, Rey JA. Naltrexone/Bupropion ER (Contrave): Newly Approved Treatment Option for Chronic Weight Management in Obese Adults. P T. 2016 Mar;41(3):164–72.Apolzan JW, Venditti EM, Edelstein SL, Knowler WC, Dabelea D, Boyko EJ, et al. Long-Term Weight Loss With Metformin or Lifestyle Intervention in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Ann Intern Med. 2019 May 21;170(10):682–90.Sherman MM, Ungureanu S, Rey JA. Naltrexone/Bupropion ER (Contrave): Newly Approved Treatment Option for Chronic Weight Management in Obese Adults. P T. 2016 Mar;41(3):164–72.Lonneman DJ Jr, Rey JA, McKee BD. Phentermine/Topiramate extended-release capsules (qsymia) for weight loss. P T. 2013 Aug;38(8):446–52.Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, Davies M, Van Gaal LF, Lingvay I, et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021 Mar 18;384(11):989–1002.Garvey WT, Batterham RL, Bhatta M, Buscemi S, Christensen LN, Frias JP, et al. Two-year effects of semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity: the STEP 5 trial. Nat Med. 2022 Oct;28(10):2083–91.le Roux CW, Zhang S, Aronne LJ, Kushner RF, Chao AM, Machineni S, et al. Tirzepatide for the treatment of obesity: Rationale and design of the SURMOUNT clinical development program. Obesity. 2023 Jan;31(1):96–110.Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, Wharton S, Connery L, Alves B, et al. Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2022 Jul 21;387(3):205–16.Jastreboff AM, Kaplan LM, Frías JP, Wu Q, Du Y, Gurbuz S, et al. Triple-Hormone-Receptor Agonist Retatrutide for Obesity – A Phase 2 Trial. N Engl J Med. 2023 Aug 10;389(6):514–26.Frias JP, Deenadayalan S, Erichsen L, Knop FK, Lingvay I, Macura S, et al. Efficacy and safety of co-administered once-weekly cagrilintide 2·4 mg with once-weekly semaglutide 2·4 mg in type 2 diabetes: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, active-c,ontrolled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2023 Aug 26;402(10403):720–30.Leung, Alice W. Y., Ruth S. M. Chan, Mandy M. M. Sea, and Jean Woo. 2017. An Overview of Factors Associated with Adherence to Lifestyle Modification Programs for Weight Management in Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14 (8). Maciejewski, Matthew L., David E. Arterburn, Lynn Van Scoyoc, Valerie A. Smith, William S. Yancy Jr, Hollis J. Weidenbacher, Edward H. Livingston, and Maren K. Olsen. 2016. Bariatric Surgery and Long-Term Durability of Weight Loss. JAMA Surgery 151 (11): 1046–55.Ryan DH, Yockey SR. Weight Loss and Improvement in Comorbidity: Differences at 5%, 10%, 15%, and Over. Curr Obes Rep. 2017 Jun;6(2):187–94.Marx N, Husain M, Lehrke M, Verma S, Sattar N. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists for the Reduction of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Circulation. 2022 Dec 13;146(24):1882–94.Lincoff AM, Brown-Frandsen K, Colhoun HM, Deanfield J, Emerson SS, Esbjerg S, et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2023 Dec 14;389(24):2221–32.Kosiborod MN, Abildstrøm SZ, Borlaug BA, Butler J, Rasmussen S, Davies M, et al. Semaglutide in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction and Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2023 Sep 21;389(12):1069–84.Karakasis P, Patoulias D, Fragakis N, Klisic A, Rizzo M. Effect of tirzepatide on albuminuria levels and renal function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and multilevel meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab [Internet]. 2023 Dec 20.Ida S, Kaneko R, Imataka K, Okubo K, Shirakura Y, Azuma K, et al. Effects of Antidiabetic Drugs on Muscle Mass in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2021;17(3):293–303.Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, Van Gaal LF, McGowan BM, Rosenstock J, et al. Impact of Semaglutide on Body Composition in Adults With Overweight or Obesity: Exploratory Analysis of the STEP 1 Study. J Endocr Soc. 2021 May 3;5(Supplement_1):A16–7.Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, Davies M, Van Gaal LF, Lingvay I, et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021 Mar 18;384(11):989–1002.Reinmann A, Gafner SC, Hilfiker R, Bruyneel AV, Pataky Z, Allet L. Bariatric Surgery: Consequences on Functional Capacities in Patients With Obesity. Front Endocrinol. 2021 Apr 1;12:646283.Carlsson LMS, Carlsson B, Jacobson P, Karlsson C, Andersson-Assarsson JC, Kristensson FM, et al. Life expectancy after bariatric surgery or usual care in patients with or without baseline type 2 diabetes in Swedish Obese Subjects. Int J Obes. 2023 Oct;47(10):931–8.Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Davies M, Van Gaal LF, Kandler K, Konakli K, et al. Weight regain and cardiometabolic effects after withdrawal of semaglutide: The STEP 1 trial extension. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022 Aug;24(8):1553–64.Consumer trends: 2024 Food & Wellness special. The New Consumer. (n.d.). https://newconsumer.com/trends/consumer-trends-2024-food-wellness/Gorgojo-Martínez JJ, Mezquita-Raya P, Carretero-Gómez J, Castro A, Cebrián-Cuenca A, de Torres-Sánchez A, et al. Clinical Recommendations to Manage Gastrointestinal Adverse Events in Patients Treated with Glp-1 Receptor Agonists: A Multidisciplinary Expert Consensus. J Clin Med Res [Internet]. 2022 Dec 24;12(1). Tantawy SA, Kamel DM, Abdelbasset WK, Elgohary HM. Effects of a proposed physical activity and diet control to manage constipation in middle-aged obese women. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2017 Dec 14;10:513–9.

The post Ozempic for weight loss: What coaches (and clients) need to know about GLP-1 drugs appeared first on Precision Nutrition.