As COVID-Era Restrictions End, Disabled Americans Want to Avoid a ‘Return to Normal’

0 View

Share this Video

- Publish Date:

- 15 April, 2022

- Category:

- Herbs

- Video License

- Standard License

- Imported From:

- Youtube

Tags

President Joe Biden hired Kim Knackstedt in early 2021 to make sure that Americans with disabilities were not forgotten as the country returned to normal after the COVID-19 pandemic. A year later, that seems to be precisely what has happened—and it’s unfortunate, Knackstedt says.

“What was considered ‘normal’ was actually not a great way to live, often,” says Knackstedt, who served as the first White House director of disability policy, before leaving the administration on March 11. “It wasn’t accessible. It actually didn’t provide all of the things that we needed to get even basic health care, and so many other things, like basic economic security.” [time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

As states and cities roll back vaccine requirements and mask mandates, companies phase out flexible work policies, and federal funding for pandemic-response measures runs out, millions of Americans who are immunocompromised or who have other disabilities or chronic illnesses that make them vulnerable to COVID-19, are urging policymakers to pump the brakes. They aren’t calling for more lockdowns or never-ending masking, Knackstedt says. Rather, they want government officials to make permanent some of the systemic tweaks that helped make everything from employment and health insurance to housing and schooling more accessible to all Americans during the pandemic.

Courtesy The Century FoundationKimberly Knackstedt

They also want to add new systems that will help make communities more accessible in the future. Their wishlist includes widespread access to COVID treatments and testing; improved ventilation systems; flexible masking policies that ramp up when necessary; and a slew of economic proposals, including paid sick leave, affordable housing and measures to help people secure disability benefits. They want, in other words, to embrace the pandemic-era shifts that allowed people with disabilities, who are more than twice as likely to live in poverty as nondisabled people, to engage more fully in many parts of society.

People with disabilities or other medical conditions represent a huge segment of the country. Nearly 3% of U.S. adults, or some 7 million people, take immunosuppressant drugs, and tens of millions more have diseases that lower immunity directly or have medical conditions that put them at higher risk from infectious disease. More Americans are joining their ranks every day: studies estimate that between 10 and 30% of people who contract COVID-19 end up with Long COVID, and some fraction of that population is likely to need ongoing economic and medical aid in the future.

“The COVID-19 pandemic spurred the largest influx of new entrants to the disability community in this country in modern history. It has been a mass disabling event and the numbers are continuing to climb,” says Rebecca Vallas, a senior fellow at The Century Foundation (TCF), who leads the think tank’s disability economic justice team. “It is at a scale that policymakers absolutely cannot ignore.”

Knackstedt, Vallas, and another disability advocate, Vilissa Thompson, are now working with a wide array of think tanks and advocacy groups, including the Century Foundation and the Ford Foundation, to push lawmakers to improve existing systems. Their targets include Social Security benefits, food stamps, affordable housing, the minimum wage, paid leave and transportation, and preserving some of the pandemic-era policy changes that benefitted all Americans.

“The question needs to be, how do we lay the groundwork for a better normal? asks Anne Sosin, a healthy equity fellow at Dartmouth College. How do we invest in the systems and policies and infrastructure we need to manage the pandemic over time?”

‘Dismissing the lives of people with disabilities’

Disability advocates started raising the alarm about the potential fallout from the pandemic in early 2020. They were used to bearing the brunt of public health and economic downturns, and as it became clear how serious COVID-19 was, disabled people started to warn that it could have similar effects to those of polio in the early 20th century: it would permanently mark a generation.

But despite the warnings from disability advocates, public health experts, and initially from Democratic political leaders who said they wanted to change the trajectory of the pandemic after the Trump Administration, much of the country seems to have decided it is no longer concerned about about the potential effects of contracting the coronavirus. Thompson, who says she’s seen both racism and ableism during the pandemic, said that lack of empathy can feel like it’s coming not just from other individuals, but from the government too.

Courtesy The Century FoundationVilissa Thompson

These tensions came to a boil in January when CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky, speaking about a study that showed very few vaccinated people died of COVID-19, told Good Morning America, “The overwhelming number of deaths, over 75%, occurred in people who had at least four comorbidities, so, really, these are people who were unwell to begin with.”

To many disability advocates, this was “another example of a governmental agency dismissing the lives of people with disabilities,” as Bethany Lilly of disability rights organization The Arc, said at the time. After significant backlash to the comments, Walensky apologized and said CDC officials would begin meeting with disability advocates regularly.

The Biden Administration has since taken steps to protect disabled people from the pandemic, including a recent presidential memorandum that directed federal agencies to develop a national action plan to address the looming crisis of Long COVID.

But many are critical of the Administration’s pandemic response overall. While most public health experts say the Biden Administration did manage the early part of the COVID-19 vaccine rollout successfully, a large number of experts—including former Biden COVID advisers—have publicly criticized the federal response in recent months.

Pandemic fatigue is real, and politicians have often said they are trying to respond to Americans’ desires to go about their lives. But Kaiser Family Foundation polling shows that Black, Hispanic and low income Americans, as well as those with chronic health conditions—many of the groups disproportionately impacted by the pandemic—still support people wearing masks in some public settings. Meanwhile, disabled people reported less vaccine hesitancy but more obstacles in getting vaccinated, and still have lower rates of vaccination than the overall population. Treatments remain in short supply. As businesses scrap mask mandates and some states banned schools from keeping them in place, parents of disabled children have sued, arguing the lack of masking puts their vulnerable kids at risk.

“What kind of people are we, when we cut loose the most vulnerable members of our community as sort of expendable?” asks Gregg Gonsalves, an infectious disease expert at Yale’s School of Public Health. Gonsalves compared the way the U.S. is treating immunocompromised people to how he saw gay men treated during the AIDS crisis. “In the AIDS epidemic, it took the president seven years to say the word, so it doesn’t surprise me that people who were considered disposable are indeed treated as disposable,” he says.

But in a pandemic, Gonsalves notes that thinking only about personal risk doesn’t work very well. “Public health is never about personal risk,” he says. This approach, he adds, “lands us in greater peril than where we were in the fall.”

Getting a seat at the table

These fears are why Knackstedt and the other disability advocates are launching a new initiative on April 21, the Disability Economic Justice Collaborative, which is designed to reach outside the disability community, into establishment policy making circles. The collaborative includes think tanks like The Century Foundation and the Center for American Progress, as well as more than two dozen other organizations across the progressive policy spectrum, such as the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, National Partnership for Women and Families, Justice in Aging, the Urban Institute, the Food Research and Action Council, and Data for Progress.

“People with disabilities have historically been viewed in a lot of ways as a ‘them’ instead of as part of the ‘us,’” Vallas says. “And so a lot of what this is really about is about saying, y’all, we were part of the ‘us.’”

Knackstedt says she was able to do some of this in her time on the White House’s Domestic Policy Council. In her 14 months there, she worked to implement Biden’s executive order on diversity, equity and inclusion in the federal workforce and helped get Long COVID declared a disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act, giving long-haulers federal civil rights protections. But ultimately the work took a toll on her physical health. “Across the entire government, whether it’s the Hill, whether it’s the Administration, there’s a lot more that can be done to make the work accessible,” Knackstedt says.

Oliver Contreras—Pool/Sipa USA/APVice President Kamala Harris meets with disabilities advocates in the Vice President’s Ceremonial Office in Washington, D.C., on July 14, 2021.

Convening this kind of group is something disability advocates have wanted to do for years, says Rebecca Cokley, a longtime disability rights advocate and former Obama Administration official. “For decades, [disability groups] were told that the reason we couldn’t do stuff was because we didn’t have money,” says Cokley, who joined the Ford Foundation last year as the philanthropic giant’s first U.S. disability rights officer. Now, she has an annual budget of $10 million and was in a position to help fund this collaboration.

This new energy is leading to initiatives like Data for Progress, which has become a go-to polling firm for liberal policymakers, standing up a disability polling project that will survey people with disabilities to help lawmakers see them as a political constituency and include more disability-related questions in its other surveys of all voters.

“Part of the power here comes from integrating disability as a lens through which we look at all policy,” says Matthew Cortland, a senior fellow at Data for Progress leading the polling project.

Advocates are hoping that having a source for public opinion data that Democratic politicians trust will give heft to their work. Already they have found some allies in Congress. Rep. Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts has frequently spoken out about disability issues and says she realized the topic’s importance when she saw a disability advocate treated “as a second class citizen” during her time as a city councilor in Boston. “That was painfully familiar to me as a Black woman,” she tells TIME. “These were injustices happening in plain view, for which there was little spotlight, focus or outrage.” Now she frequently communicates with disability advocates, and recently introduced a bill with Sen. Tammy Duckworth of Illinois that aims to improve access to Long COVID treatment and clinics.

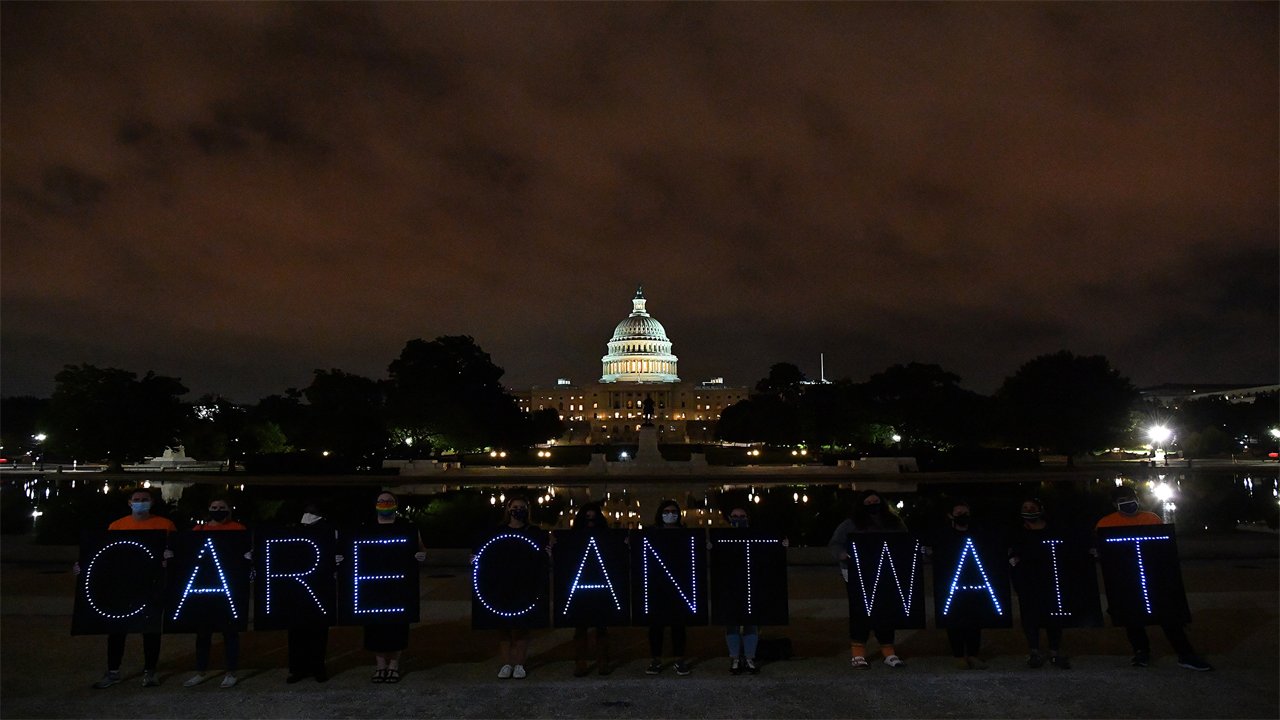

Larry French—The Arc of the United States/Getty ImagesDisability rights activists and caregiving advocates hold a vigil in front of the U.S. Capitol, urging Congress to include full federal funding for home and community based care services in the Build Back Better budget package in Washington, D.C., on Oct. 06, 2021.

Other lawmakers like Senator Elizabeth Warren have also been vocal about disability issues during the pandemic. “All policy issues are disability issues, and our laws should reflect this reality. This pandemic has reinforced what I’ve argued all along: when leaders implement policy to support the most vulnerable in society you improve life for everyone,” Warren said in a statement.

The White House recently replaced Knackstedt with Day Al-Mohamed, another disability advocate who most recently worked at the Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Knackstedt hopes Al-Mohamed will be able to build on the foundation she started last year.

Thompson, who is a Black disabled woman and trained as a social worker, adds that she hopes the collaborative can help policy makers understand the way that people with disabilities are often affected not just by their disability but by issues of race, class, gender and sexuality as well.

“Diversifying the people who are able to be there is really critical so that we can have a more comprehensive, inclusive understanding of these policies,” she says. “Instead of policymakers or politicians talking at us, we’re at the table working with them.”

‘A wholesale paradigm shift’

Advocates say the large number of people affected by COVID could make it hard to ignore. More than 980,000 people have died in the U.S., and many more are grieving them. As of March, there were more than 1 million disability benefits cases pending with the Social Security Administration. Even if people don’t enjoy thinking about these statistics, they are having a significant impact on the American psyche and the country’s economy. “My hope is that as we are continuing to beat the drum on long COVID,” says Mia Ives-Rublee, director of the Disability Justice Initiative at the Center for American Progress, “it brings some attention to some programs that have been left to wither on the vine.”

Courtesy The Century FoundationRebecca Vallas

Vallas of the The Century Foundation sees incorporating disability policy into every other area as part of the key. If disabled people are in policy conversations about pandemic preparedness and housing and Social Security and equal pay from the beginning, then she hopes that could move rules and laws in a new direction. Before the pandemic, disability advocates had started to make some progress.

In 2016, Hillary Clinton devoted a speech during her campaign entirely to disability rights. In 2020, all of the major Democratic presidential candidates released disability policy platforms for the first time. By 2024, Vallas would like to see disability considerations baked into economic policymaking across the government, and by 2028, the team hopes all presidential candidates of any party will put forward a disability platform. Eventually, they’d like to reduce poverty for disabled people across the country—but for now they want to use the pandemic-inspired momentum while they can.

“It must be a wake up call,” Vallas says. “This must also be a moment that our policymakers understand as calling out for a wholesale paradigm shift.”