Exclusive: For the First Time, New Tech Enables Paralyzed Man To Move and Feel Again

0 View

Share this Video

- Publish Date:

- 30 July, 2023

- Category:

- Holistic

- Video License

- Standard License

- Imported From:

- Youtube

Tags

>

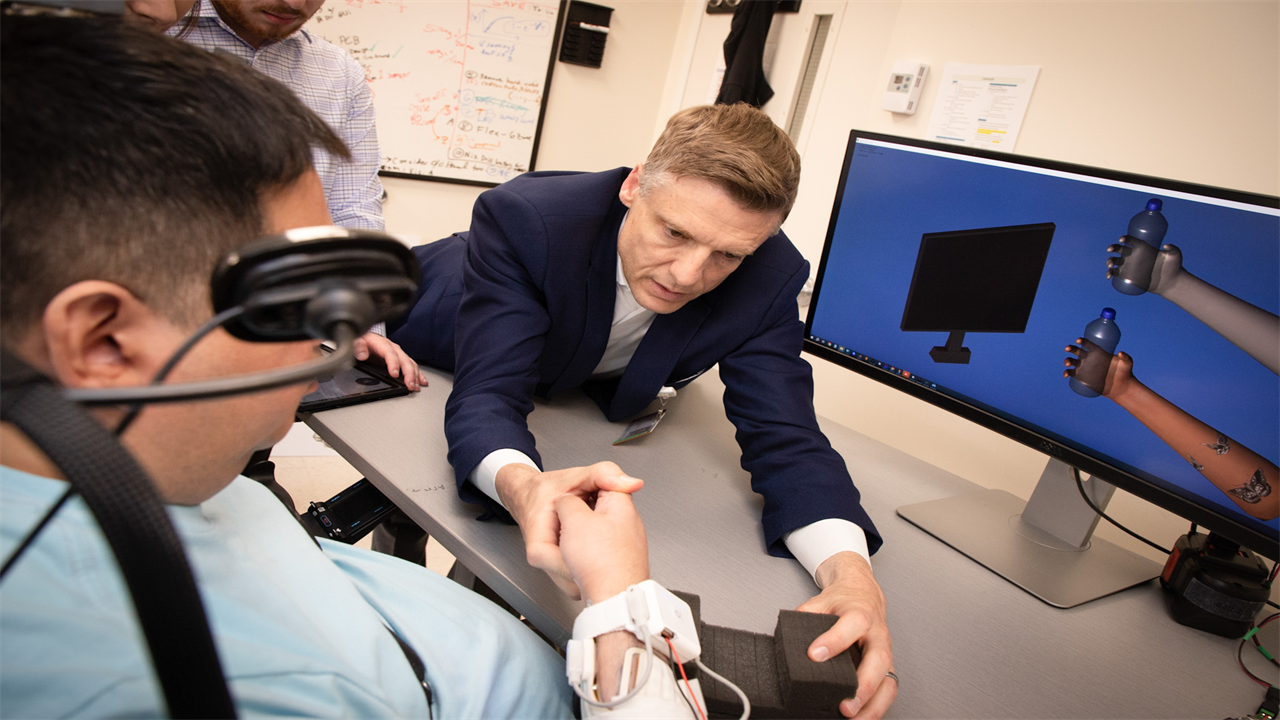

A cluster of researchers surround 45-year-old Keith Thomas, their eyes fixed on his right hand. “Open, open, open,” they urge, cheering when his fingers flutter out to mirror an image on a computer screen and again when they begin to curl back inward.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]Thomas, who was paralyzed from the chest down after a diving accident in July 2020, is able to move his hand again thanks to a cutting-edge clinical trial led by researchers from Northwell Health’s Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in New York. Chad Bouton, a bioengineer at the Feinstein Institutes who is leading the trial, says he believes Thomas is the first human in the world to receive a double neural bypass, a technology that links his brain, spinal cord, and body in hopes of restoring both his ability to move and his sense of touch—even outside the laboratory.

So far, the therapy seems to be working. Thomas is now able to lift his arms and can feel sensations on his skin, including the touch of his sister’s hand.

“It’s indescribable,” Thomas says, “to be able to feel something.”

When Thomas began working with Bouton’s lab in 2021, he couldn’t lift his arms off his wheelchair frame. For about a year, to help Bouton and his team get a sense of his baseline post-accident function, Thomas’ primary task was to watch hands moving on a computer screen and try to copy their motions. Much to his frustration, his body couldn’t match his mind’s commands.

That changed after a 15-hour surgery in March 2023, during which neurosurgeon Dr. Ashesh Mehta placed five tiny, fragile electrode arrays in the hyper-specific regions of Thomas’ brain that control motion and feeling in his right hand and fingers. To confirm he’d found the right spots, Mehta awakened Thomas during surgery and stimulated those areas of the brain. Immediately, he says, Thomas could feel some of his fingers for the first time in almost three years. “It was a very good feeling,” Mehta says.

Now, when Thomas thinks about moving—imagining himself squeezing a bottle, for example—the arrays transmit the electrical signals in his brain to an amplifier on his skull, which via an HDMI cable passes the signals on to a gaming computer sitting a few feet away. The computer decodes those messages and sends a signal to electrodes placed on Thomas’ skin, which stimulate the muscles he needs to perform the motion he’s envisioning. The whole thing happens almost in real time, though it takes effort on Thomas’ part to imagine and attempt the movement.

This process feels harder on some days than others, Thomas says, and it’s not always clear why. But after all those months of staring at hands, Thomas can finally use his. “It’s mind-blowing,” he says.

Along with motion, Thomas is also regaining a sense of feeling. When he touches an object or person, sensors on his skin send a signal to the computer, which then communicates with the arrays in his brain. He can now feel a hand in his, or a feather stroking the sensors on his fingertips. Touch doesn’t feel exactly how it did before the accident—Thomas describes it as a burst of energy—but it’s progress.

“Touching someone’s hand and feeling that is such an important part of life,” Bouton says. An accurate sense of touch is also essential for carrying out functional tasks, like buttoning a shirt or holding a styrofoam coffee cup without crushing it.

Thomas’ case shows how far paralysis research has advanced in the last few decades. About 20 years ago, researchers began demonstrating that brain-computer interfaces (BCIs)—like the one now used by Thomas—could help people with paralysis perform tasks using their thoughts. About a decade later, building upon research that showed humans with paralysis could use their thoughts to control robotic limbs, Bouton and his team used a neural bypass to restore movement, but not sensation, to the arm of a man who had been paralyzed in an accident.

In the years since, research teams have used spinal-cord stimulation to restore mobility to people recovering from accidents or strokes. And earlier this year, a scientific team reported that they’d helped a man with paralysis begin to walk naturally again by creating a bridge between his brain and spinal cord.

The new trial with Thomas (results from which have not yet been published in a scientific journal) pushes the field forward by “combining all the elements—brain, body, and spine—and movement and the sense of touch,” Bouton says. Unlike in his previous neural-bypass work, Bouton adds, Thomas is slowly but surely relearning to move and feel even when he’s not attached to the computer system in the laboratory.

That’s thanks to the extra connection between his brain and spinal cord, in addition to the bridge between his brain and body. Each time Thomas performs a motion when he is attached to the computer, the system stimulates the portion of his spinal cord that sits just below his injury—essentially, reestablishing contact between his brain and spinal cord and helping his body train to again move and feel on its own. “That electrical stimulation, we believe, is awakening circuits that have been damaged and dormant for three years,” Bouton says.

Only a few months post-operation, Thomas is able to move his arms when he’s not connected to the computer and can describe where on his arm he’s being touched, even with his eyes closed. The team has also observed small natural movements in his fingers, another good sign.

Thomas’ spirits are up, he says, now that he can see his accomplishments during his twice-weekly visits to the Feinstein Institutes, which he spends cracking jokes and listening to his favorite musician, Harry Styles. Thomas is motivated to keep going both by his own gains and by the promise of pioneering a technology that could someday help others, he says.

Widespread adoption of neural bypass technology is likely a ways off; it’s taken millions of dollars in research funding and a team of dozens to get Thomas to this point. (The clinical trial that Bouton is running aims to test the technology in up to three people, but Thomas is the first to be implanted.)

In hopes of benefitting a larger group of people, Bouton is also working on a separate, non-invasive system meant to stimulate movement through electrodes placed on the skin—no surgery required. Bouton says such a product could be a good fit for people with less-extensive paralysis, such as those who have suffered a stroke, or who don’t want to undergo brain surgery. If the system works for those populations, Bouton says, “now you’ve opened up the door to millions and millions of folks around the world.”